China’s urbanization visualized: The growth of Chinese cities and why it shows market potential

Much of China’s market potential is still latent. This visualization shows the explosive growth of China’s cities.

With a population of over 1.4 billion, China is currently the most populous nation in the world. After reaching a population of 1 billion in the early 1980s, China’s population growth rate slowed down and is now close to zero. Despite slower national growth rates, Chinese cities have experienced a tremendous increase in size, both in population and area in the last forty years. Some of the world’s largest cities are now located in China. The growth of Chinese cities has had a major impact on China’s economy and its relationship with the world. Along with China’s urbanization comes a rising middle class, and increasingly sophisticated consumers even in lower tier cities.

[Two views of Chengdu’s Gaoxin District. The first photo, taken in 2000, shows the Min River flowing between farms, small villages and an occasional factory. Chengdu’s Third Ring Road, Beltway and Renmin South Road are all under construction in the photo. In the second photo, taken in 2016, the scene has completely changed. At the northwest corner of Renmin South Road and Chengdu’s Beltway is the Global Center, a large shopping, entertainment and office complex that is conveniently the world’s largest structure. Also worth noticing in the photo are the number of high-rise apartment buildings and changes to the flower of the Min River. Chengdu’s rapid urban growth exemplifies the growth of Chinese cities. Source – Google Earth]

Urbanization of the Tri-cty area, Guangdong 1993 to 2016

[Animated image of the tri-cities area of eastern Guangzhou, including Shantou, Jieyang and Chaozhou. Between the late 1980s and 2016, the area experienced rapid urban growth as the three main cities expanded their borders, eventually creating one large Chinese metropolitan area of some 14 million people. Source – Google Earth]

The rapid growth of Chinese cities was first concentrated in coastal areas such as the corridor stretching from Beijing to Shanghai and south to Guangzhou. Later, the pace of China’s urbanization sped up across provincial capitals in the rest of the country, benefiting large inland cities such as Wuhan, Shenyang and Xi’an. Now, the growth of Chinese cities is beginning to manifest itself in smaller second- and third-tier cities across the country, including Yangzhou, Baoji, Nanyang, Putian, Zunyi, etc.

These cities may sound obscure and unmemorable, but they all have populations in the millions. Every year, their population and GDP grow and their citizens therefore become more wealthy. For example, the urban area of Yangzhou has grown from a little over 500,000 in 1990 to nearly 2 million today. During the same period of time, Yangzhou’s neighboring city of Taizhou grew from 250,000 to nearly 1.5 million. Between 2007 and 2018, GDP per capita increased fourfold in the region, likely a result of the rapid urbanization the cities experienced during the past few decades. As cities like Yangzhou and Taizhou continue to grow in population and wealth, the potential to do business increases.

Urbanization of Guangzhou to Dongguan 1984 to 2016

[Animated aerial view of Guangzhou, Foshan and Dongguan taken between 1984 and 2016. In the 1984 image, the grey built up area of Guangzhou is visible along the banks of the Pearl River, while Foshan and Dongguan are merely dots on the map. After the Reform & Opening up Policy’s effects start to accumulate, urban growth explodes in the region until the three cities are connected by city. Source – Google Earth]

The rise of Chinese metropolitan areas is shifting and propelling the Chinese economy as well as the growth of Chinese cities

The rapid growth of Chinese cities and the relative proximity of these cities to each other has led to a number of emerging Chinese metropolitan areas. One of the most obvious examples is the Pearl River Delta, which has developed in a cluster of many large cities, including Guangzhou, Dongguan, Foshan, Shenzhen, Hong Kong and Macau. More than 100 million people live in the Pearl River Delta.

Another example is the Yangtze River Delta, or the “Jiangnan” region, which includes Shanghai and cities in neighboring Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces. In the visualization below, it is apparent that the whole Jiangnan area is merging into one urban mass.

Urbanization of Jiangnan 1985 to 2016

[Shanghai, Suzhou, Wuxi and northern Zhejiang collectively known as Jiangnan, are merging into one giant metropolitan area. The industries involved are cash crops like rice, tea, soybeans, while also serving as a portal to the outside world. Zhejiang is one of China’s largest export bases and e-commerce hubs. From 1985 to 2016, we can Shanghai gradually reaching out to Suzhou, and pockets of development in between cities. – Google earth]

These clusters of cities have given rise to commuter belts, where people spend less on rent, but are still able to work in the city. A notable example of this is Kunshan, a city in Jiangsu province close to border with Shanghai. Due to lower housing costs in nearby Kunshan, many Shanghai residents are deciding to live outside of the city and commute every day, sometimes spending hours on trains, metro and bus.

Urbanization of the Pearl River Estuary (Hongkong, Shenzhen, Macau) 1986 – 2016

[Animated aerial view of the Pearl River Estuary. In the late 1980s, the main built-up urban areas were Hong Kong and Macau, visible on the bottom right and far left of the image. Between the early 1990s and 2016 however, Shenzhen’s astounding growth came to overshadow its neighboring cities, which is captured in the upper right portion of the image. In the early 2000s, Shenzhen developed westward into the Pearl River Estuary on massive parcels of reclaimed land. Also visible in this animation is the construction of Hong Kong’s airport built on reclaimed land and the Hong Kong-Macau-Zhuhai Sea Bridge.]

In conjunction with the rapid growth of Chinese cities, the rapid development of China’s high-speed rail network has benefitted the growth of Chinese metropolitan areas as it has made it possible to commute longer distances to work. The first high-speed rail line in China connecting Beijing and Tianjin, two neighboring cities, opened in 2008. Today the network is near 30,000 km in length. This vast network has benefitted local residents, foreign tourists and commuters alike.

Wuhan and the cities surrounding it exemplify the converging trends of improved intercity high-speed rail networks and emerging Chinese metropolitan areas. About 50 kilometers from Wuhan is Xiaogan, a city with a population of roughly 5 million. Despite the distance between the cities, a high-speed rail trip makes the journey between the two cities possible in 28 minutes. About 80 kilometers in the other direction from Wuhan is Xianning, a city of some 4 million people. The city of Huanggang (7 million residents) is also connected to Wuhan by a 30-minute high-speed rail service. Combined together with Wuhan, these cities have a population of over 25 million people.

Wuhan is not the only emerging Chinese metropolitan area to benefit from the growth of high-speed trains, however. Chongqing and Chengdu are linked to a plethora of smaller cities across the Sichuan Basin by more frequent and faster trains. Kaifeng, Luoyang and Jiaozuo are all connected by high-speed rail services to Zhengzhou. The list of emerging Chinese metropolitan areas interconnected by high speed rail goes on and on.

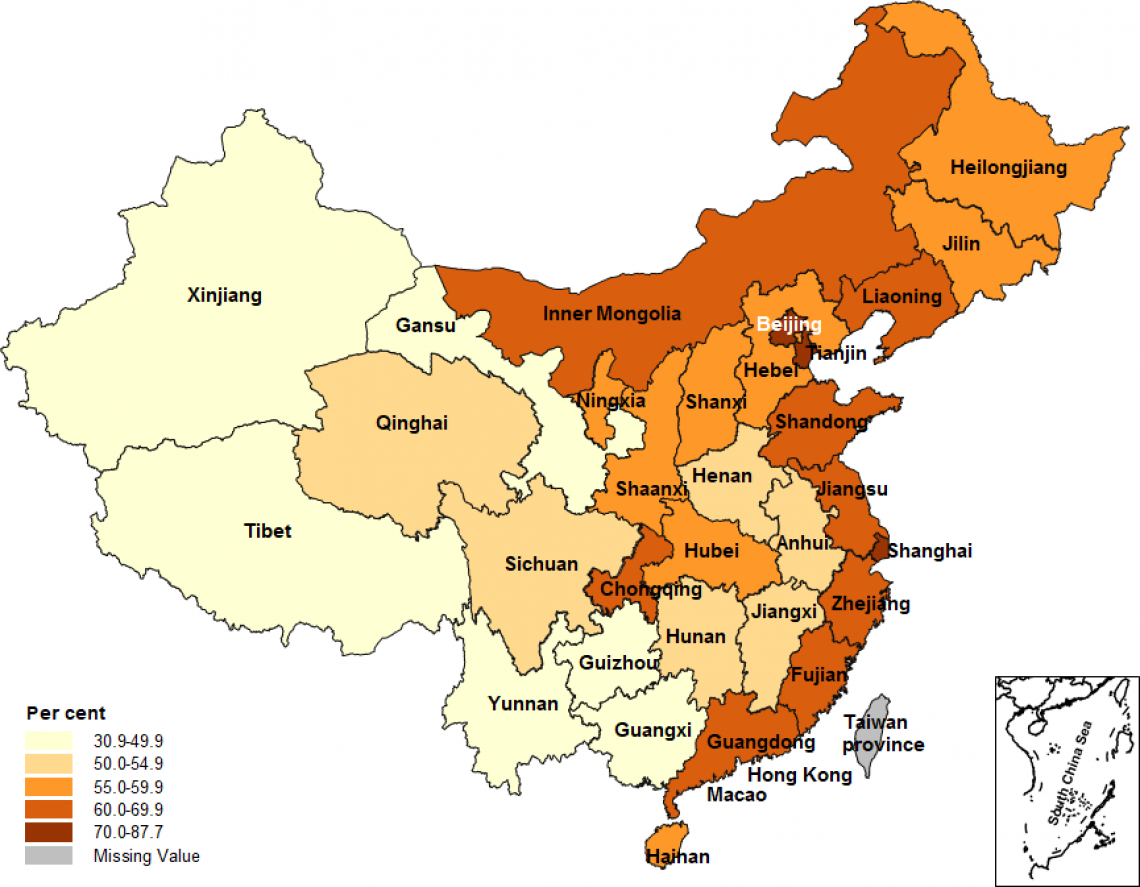

[This 2017 map shows China’s urban to rural population ratio by province. Notable provinces are Sichuan, Yunnan and Guizhou. These provinces’ relatively low ratios and large populations offer insights into the potential of further urbanization. Source – UNICEF ]

China’s low urban to rural population ratio means that second- and third-tier cities have great potential

In addition to increased mobility between China’s metropolitan areas, Chinese cities still have more room to grow. China’s urban to rural population ratio was 13.3% in 1950. Today, it is around 60%. This huge increase in urban population has happened all over China, but mostly in China’s wealthier coastal cities. Despite high rates in some provinces, urbanization is still taking place across the country, in some places more than others.

As seen in the graph above, some highly populated provinces still have a low urban to rural population ratio, suggesting that the potential for further urbanization in these provinces is quite great. For example, more than 30% of Shandong’s 100 million residents still live in rural areas and more than 45% of Henan’s population of 95 million people still lives in rural areas. Provinces such as Sichuan, Guizhou and Yunnan in Southwestern China have even larger amounts of rural residents expected to move into the city.

Foreign companies looking to expand in China may benefit from remembering that some provinces have a lot of catching up to do when it comes to China’s urban to rural population ratio. These cities, not always on the coasts, are likely to bring. Watch Luzhou’s urban area explode in the GIF below.

Urbanization of Luzhou 1988 to 2016

[Animated aerial view of Luzhou, a third-tier city located on the Yangtze River between Chongqing and Chengdu. Starting in the early 1990s, the imagery shows a small town between the Yangtze and Fu Rivers that quickly expands beyond its borders. By 2016, Luzhou had expanded well beyond four times its size in 1990. Luzhou is exemplary of many other third-tier cities across Southwest China, including Mianyang, Nanchong, Liuzhou, Anshun and Qujing.]

The growth of Chinese cities fuels growth across markets

Some Chinese cities have multiplied many times in size over the last forty years. Others have yet to do so. What is certain is that the people living in newly built neighborhoods in Chinese cities boost demand in a number of markets. Whereas markets in tier-1 and tier-2 cities are reaching saturation, a majority of China’s consumption potential remains in lower tier cities, inland provinces and future urbanization. These developing areas are proving to be valid options for China market entry.

Real estate companies, construction companies and infrastructure companies have been some of the most obvious beneficiaries of China’s urbanization. As Chinese cities sprawl, they require newly constructed roads, mass transit, and most obviously, apartment blocks. Between 2007 and 2016, the number of newly built apartments across China increased from 4.4 million to 7.5 million. These apartments have in turn fueled growth in many other markets, such as furniture, which has grown by 10% annually since 2014, and interior design.

As Chinese cities spread outwards, the burgeoning Chinese middle class have invested in ways to transport themselves. In areas where public transport has not caught up with urbanization, there is a strong demand for vehicles. Vehicle sales in China have surged from under 250,000 units in 2000 to over 2 million units today.

In addition, a surge in mass transit investment has also accompanied the growth of Chinese cities. In 2011, cities across China invested approximately 160 billion yuan in mass transit. By 2017, that amount had ballooned to nearly 500 billion yuan. As Chinese cities continue to expand outwards, this amount is likely to continue growing.

Besides home furnishings and transportation, another market that has benefited form the China’s urbanization is property insurance. Between 2013 and 2017, the market’s average annual growth rate was more than 20%. Despite a slowdown in the past few years, the market is likely to continue growing at a fast rate as Chinese consumers buy more and more properties.

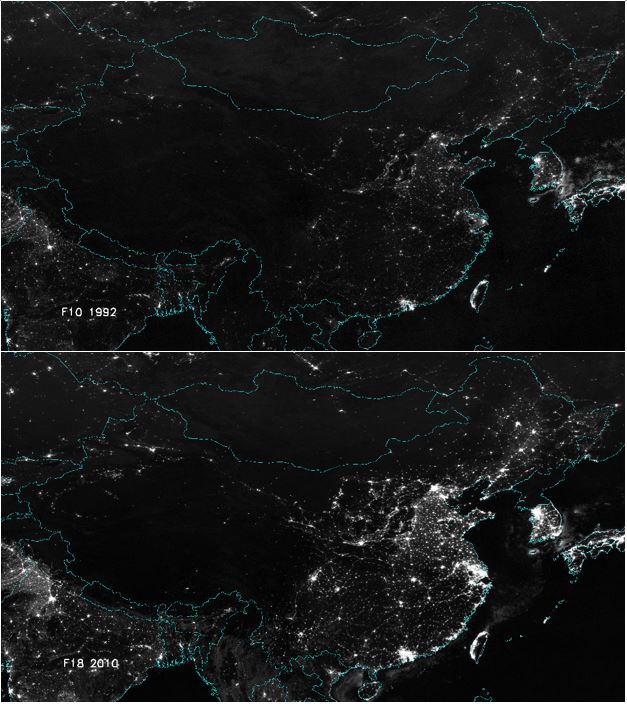

[Two night-time satellite views of China. In the first image, taken in 1992, much of China appears dark, with a few bright spots, indicating the extent of urbanization at the time. By 2010, the bright areas had spread remarkably, showing the intense growth of Chinese cities and China’s GDP. Source – National Geophysical Data Center]

What does the China’s urbanization cities mean for international brands?

Brands seeking opportunity from China’s rapid economic growth should not overlook developing areas in their long term China market strategy.

When foreign companies look to expand in China, it is tempting to look mainly to first-tier cities on the coast as well as provincial capitals. These cities are the largest cities in China and they do command some of the largest pockets of wealth in the country. However, companies would do well to notice the large changes that are taking place in dozens of other cities across China. These cities hold massive potential because their combined population and wealth is so great.

The potential of cities like Luzhou, Jieyang and Nanchong is no secret. McKinsey & Company estimates that cities of this size will contribute 40% of world economic growth during the next fifteen years. As developed markets become saturated, companies may do well to look to these emerging cities. To learn how your company can maximize potential as millions of Chinese become middle class consumers, contact our project team at dx@daxueconsulting.com

Stay on top of China’s business world with the China’s business podcast China Paradigms